Periodic Table: The Best 1990s Video Game Magazines from EMAP

Last Updated on March 1, 2024

By about June of 1993, it was estimated that in the U.K. there were already more monthly magazines than people born to read them, video game magazines included. They were a constant thing back then, like someone coming into the house and asking if anyone has taken any messages over the phone.

Well I didn’t take messages, but I did read video game periodicals, especially if they came from EMAP. They were firing on all sorts of video game cylinders through the 90s and I have a list to prove it.

Let’s start with an agreeable one.

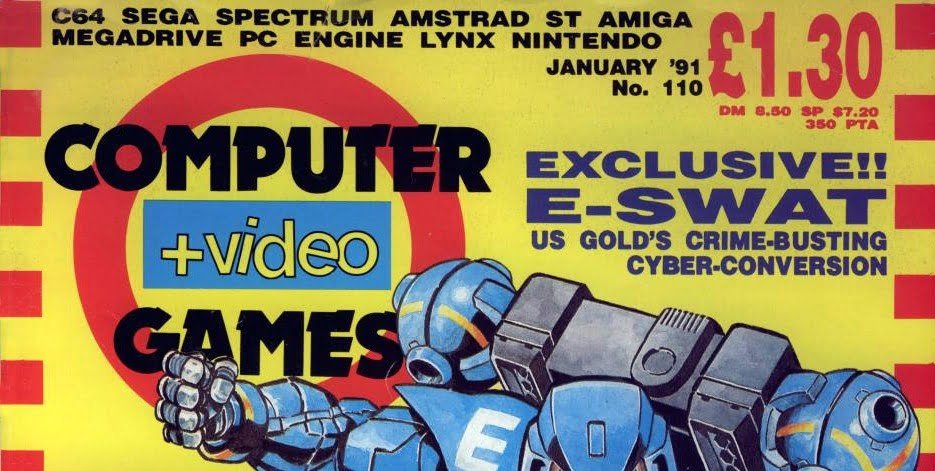

1. Computer and Video Games

The original games magazine, and sometimes the best, depending on the editor at the time. They were always upbeat about the industry that they were covering, and I got around to getting it monthly about the time that fresh editor Paul Davies was applying substantial changes to the design and scoring system.

Apparently there were complaints from people, but I loved it. The pages were bright and affectionate for both the games and the culture thereof. The editorial was replete with anonymously written information about the writing team, and even the contents page was filled with enthusiasm. It was a tone that pervaded the news, previews and reviews, and would frequently pique with appeals to the Japanese import craze, which in the mid-nineties meant they were keen on the Saturn. Weren’t we all? That’s rhetorical of course as I understand that very few people were, but Computer and Video Games played up Sega like absolute champions.

They played up most things. Not to suggest that they reviewed loose, but they were positive for the industry and were not perched over it with critical talons and an unjust sense of pride. They were tight about poor PAL conversions though, showing that they had their house well and truly in order.

Like some nerdy Bash Street School, there was something of the comic to what Computer and Video Games became under Paul Davies and company. They had the keys to the kingdom, heralded good news and effectively gave birth to a litter of other EMAP publications and writers.

2. Mean Machines

Initially an internal section of magazine inside C&VG, Mean Machines got its own publication in 1990 under famed editor Julian Rignal and became Mean Machines Sega by 1992. It was uproarious in approach; if Computer and Video Games were the Bash Street Kids then Mean Machines was Dennis the Menace. Packed with attitude, but also with a heavy hand of cheek, much of which was from Art Editor Gary Harrod and his staff writer illustrations.

The average page of this publication was bursting to the margins with flourishes of details and critical fandom. And there were a lot of pages, as befitted the sheer amount of consumer products that were available at the time. A couple of years in and the magazine made that switch and became Mean Machines Sega, confirming the cosy and beneficial relationship between EMAP and Sega, which would lead to EMAP gaining official status with Sega Magazine (and subsequent Sega Saturn Magazine) alongside Mean Machines Sega.

Mean Machines would also give us the staff writer Richard Leadbetter, who would go on to dominate high-end, mid-nineties games magazines. Taking the enthusiasm that C&VG and Mean Machines had brought and attaching it to something wholly definitive in the form of Maximum.

3. Maximum

Go one better seemed to be the approach of Maximum, and you could tell so from the flickiest of flick-throughs. Greater depth of coverage, greater screenshots, greater quality of paper, and all within a layout with more gravitas than the most sober of Sunday supplements. My brother bought a copy of issue 1 in time for him to get a PlayStation just after launch and I was sold.

Maximum understood the medium and the mediation of it better than anyone, upscaling the detail of coverage with their enormous and perfectly formatted Showcase features, but leaning the writing more maturely through the joy-of-games approach which had done EMAP well to this point.

It was quite pared back in terms of sections; Showcases led to News and then Reviews. There were previews of an occasion, but when a news update on a game could run to six pages and much space for text, you were never going short. Indeed, just to sit down and read a Showcase was a commitment. Talking points were not reduced to box-out pieces of a few sentences; they were long with paragraphs, each one building on the last to create a more unbroken picture of the game.

The attention span-deficient games magazines of our youth were growing up just as the machines around us were, and I thought Maximum was at the head of the table. There was Edge magazine as well, but Edge was always far too much the critic and much too little the participant for my taste; but then what did I know, as Edge continues to be published to this day and Maximum ran only to a resplendent seven issues over one year of publication.

Having closed, Richard Leadbetter was moved across the office to take over the reins at Sega Saturn Magazine, taking the philosophy of Maximum with him near-wholesale.

4. Sega Saturn Magazine

Truth be told, EMAP did a far better job at promoting the Saturn than Sega Europe ever did. Their writers and editors understood what the console had to offer and going into the latter half of the nineties, Sega absolutely ruled the import-chic scene due to abandonment by Sega of their customers outside Japan.

Sega Saturn Magazine followed this course and ended up writing Showcases for import titles as though they were PAL releases. Dead or Alive, any number of Capcom/SNK fighters, even Japanese RPGs. The tone was a little more laddish than Maximum, but the spirit of investment that the writers put in was of the same stock. Convincing enough that I considered buying the much heralded Grandia despite knowing nothing of Japanese language because Richard Leadbetter had written a comprehensive guide in the magazine.

An underappreciated machine at the time, the Saturn not only had qualities in itself, but the official magazine was well ahead of its rivals. The official PlayStation magazine was a demo disk with a magazine attached to it. When Sega Saturn Magazine ran an issue with a demo disk they did things like give away the entire first disk of Panzer Dragoon Saga, because they were fans and the console needed all the extra support that whomever at Sega wasn’t giving.

Somehow the magazine kept going into the autumn of 1998 and held good sales, but had almost no advertisement money to hold those sales together. Its time had come and with it the end of EMAP’s periodical greatness. Paul Davies would see another year at C&VG but Julian Rignal was out of the trade and working internally within gaming.

They got out early it turned out, as the internet was about to happen proper style, and all heck was going to break loose.

John is a writer and gardener. He comes with various 90’s Sega attachments and is the author of The Meifod Claw and other works. His favorite tree is a copper beech and he would like his coffee black without sugar, thank you.