Catching Snatcher: Thirty Years in the Waiting

Last Updated on January 26, 2024

A point-and-click adventure. Of all the genres bleating at the margins, I always found this one to be at the furthest reaches of my understanding. Just pointing and clicking and then a little bit of text. It didn’t even sound good to me in a counter-intuitive sense. Like a comic book with something almost representing gameplay grafted to it. I actively associated these games with the Personal Computer crowd and just as actively dissociated myself from all of it, happy with my choices.

But there was one game, and it wasn’t even on the PC. It got talked about as reason enough to own the machine it played on. Now that turned out to be the Mega CD, so the top tier award wasn’t exactly overflowing with entrants, and more to the point I didn’t even own the Mega CD. I had a Mega Drive, and to be honest, from the pictures I saw, I didn’t understand why it wasn’t on that.

It was Snatcher and I am not surprised that it has the legacy that it does; you could feel it coming to a simmer at the time. It was around late 1994 that it started and I had watched Akira the year before, and a lot of times quickly thereafter. I was sold on Cyberpunk as a hyper-lurid aesthetic and Snatcher had those signals on broadcast. Heck, it was broadcasting just about every populist Sci-fi concept it could get away with, but the pictures in the magazines suggested an identity of its own. That would turn out to be the hand of auto-auteur in chief, Hideo Kojima, himself coming to a simmering presence with this game.

Thirty years on, I have found this out. But did I enjoy it?

We’ll do the easy stuff first.

Vaguely interacting with Snatcher

Set for the most part within the inner and outer confines of Neo Kobe in the year twenty-forty… something… take your pick. You play as Gillian Seed, although as you can probably sense, I am using the word play very loosely. You vaguely interact with the game via the character of Gillian Seed would be a better approximation. But no matter because we are going to continue. I have watched hours of this on YouTube, so that is going to happen.

So… Neo Kobe, registered Cyberpunk centre of the Earth and home to both skin-stealing robo-wretches known as Snatchers, and Junkers, the gung-ho trench-coat Police gang out to hunt them down. Sounds familiar? Don’t worry, Snatcher is playing faster and looser with its cinematic references than I am for your attention in describing them. If you remember it, so did Hideo Kojima.

But then to be fair, he better realised his vision of it than you or I likely would. And he had CD-quality sound on his side, which by goodness he was going to use. A thorough intro sequence sets the background story in motion before some exuberance of saxophone takes you on a spirited jaunt through various colourful location shots of Neo Kobe, each one either more Bladerunner or Akira than the last, with the music seemingly taken from a drawer marked “Lethal Weapon.” A great start, I thought, and far more engaging in delivery than the FMV intro styling, which would come to dominate the following few years.

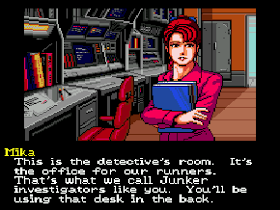

Then, without much pause, you are thrown into your first assignment as Gillian, and the whole procedure begins with a rigorous tour of the Police HQ, where you will learn the most important lesson of being a Junker; extensive menu management, which is where the rub lies.

I have written before that games are like games and books are like books. To my mind the idea that a video game can be compared to or as good as a novel is pointless and misunderstood. They may share themes but differ so much in execution that under no taxonomy do they have parity.

Books joyously explore your interaction with words and video games make something cool happen when you press a button, the good ones anyway.

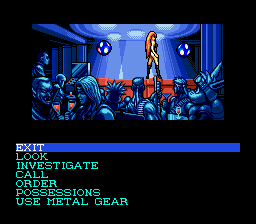

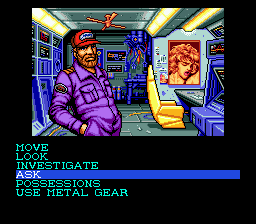

Point and click, text adventures and visual novels push me to the limits of my feelings about this. They have the words and they have the buttons. But do they really have either? I may have only watched Snatcher, but it is clear that the buttons are used largely to navigate a maze of sub-menus until you happen upon the correct logic sequence and the current conversation or story beat can move on. It is a staccato process that simply doesn’t use buttons as instant gratification common to most games, or to simulate the natural flow of a conversation. It is bad design and many an RPG had already navigated this path better before Snatcher.

But the good news is that the aesthetics and sound design of this adventure are high-punk and carefully curated. The Mega CD was always a little punchier with pixels than the machine it ran off and Snatcher combined this with a good amount of speech sampling. It’s not amazing quality, but you can feel what would become the CD generation to follow right on its heels. In fact, it pretty much released at the same time as the Saturn and PlayStation in Japan, and in those early months those machines could have done with some of Snatcher’s style.

Drenched in Cyberpunk and loaded with detective fiction, this art style will have you by the time Gillian says goodbye to his ex-wife about two minutes in. Part anime, part western panel art, Snatcher goes for colour tone and largely ambient music over complexity. High street to ever higher rising buildings, its grubby world a mesh of both corporate and home-spun punk, ever reminding you of its varied inspirations as Gillian plays the good detective and interacts with society at all levels and all times of day and night. No wonder there’s all that saxophone.

There are proto-typical Kojima character designs too, each distinct and varying between the lank and the lusty. Certainly not faces you are going to forget in a hurry. For all the nods to what has come before, this game does quickly take on a distinct identity of its own, threading itself into the weave of classical cyberpunk.

But does it legitimise point-and-click adventure in my eyes?

Free to disregard

I like how comics and graphic novels bring together language and art. To be clear, I do not like ninety-nine percent of either, but there have been examples. Akira again, or Road to Perdition and a little assortment of other manga. They do pretty much what Snatcher does, without resorting to interactive menus at a DVD level.

Now, if you find the idea of menu navigation to be as good as gameplay, and you are certainly free to, then disregard what I have just said. You are going to love this thing if you haven’t played it already. But otherwise, yes, I am suggesting that Snatcher would have been even greater as a graphic novel than a video game.

But, it is all there and I am glad to have finally caught up with it, as good as thirty years along. Certainly intrigued enough to give a watch-through of Kojima’s follow-up, Policenaughts a go. If there’s some more saxophone I’m i

John is a writer and gardener. He comes with various 90’s Sega attachments and is the author of The Meifod Claw and other works. His favorite tree is a copper beech and he would like his coffee black without sugar, thank you.